Fimbriae, Fibrils, Sex and Fuzzy Coats

The Limitation of Light

One of the frustrating aspects of working with bacteria is that they are so small that it is almost impossible to see anything other than their shape when looking down even the very best of optical microscopes. Even then, their refractive index is so similar to that of water that they have to be stuck to a glass slide, killed and stained before even their shape is revealed. Microscopes which can make use of polarized light (Phase contrast microscopy) can be used to see living bacteria but apart from the added ability of seeing some species happily swimming around they add little to what we can see using conventional staining techniques.

The fact that some species could move quite rapidly intrigued many early microbiologists and eventually some special staining procedures lead to the discovery of thin whip-like appendages which they called flagellae and conferred motility. This is not to say that light microscopy is not useful. It remains an essential tool in any bacteriology laboratory but it should be recognized that the information obtained, although extremely helpful in routine work, is limited.

Electron Microscopy Reveals More

The invention of the electron microscope revealed much more detail of bacteria. Compared to the fascinating structures uncovered in eukaryotic cells, bacteria, both inside and out, were pretty uninteresting. It wasn’t until the early 1960s that some interesting surface features of some bacterial species were noticed. This delay was partly due to the electron microscopy techniques in use at that time. The convention at the time was to use ultra-thin sections of tissue, far thinner than sections used for light microscopy. It seemed normal then to prepare bacteria in the same way. Using these techniques, the outer surfaces of bacteria seemed fairly barren but the technique did reveal some of the double membrane-like composition of Gram-negative bacteria.

Shadow-Casting Reveals Still More

Although thin sections of bacteria did not allow flagella to be seen in their entirety it did reveal interesting cross-sections which showed their internal structure. It also enabled detail of flagella attachment to be demonstrated. It was not until electron microscopes were used to look at whole cells rather than ultra-thin sections that more progress was made. This change required the development of new staining techniques known as shadow-casting where bacterial surfaces were sprayed with electron-dense material such as gold or carbon at an angle. This highlighted the fine surface structures in a way exactly analogous to light falling on a stone surface at an angle reveals more detail than light falling on it at right angles.

Shadows, Flagellae and Fimbriae

Once shadow-casting techniques had been developed the whip-like flagellae were the first to be examined in detail but one researcher in particular noticed the presence of previously undreamed of structures on the surface of some species. The person who first described these structures which he found on strains of Escherichia coli and Salmonella was Professor James Duguid. He called them fimbriae.

What are Fimbriae?

Fimbriae are thin, hair-like, projections made of protein sub-units. A number of different types have been described (about 7 at the last count, labeled Types I-VII) which can be distinguished by their size (length and diameter) and the type of antigens they carry. They are characteristic of some Gram-negative bacteria such as Escherichia coli and Salmonella spp and were first described back in the 1960s by JP Duguid who was the Professor of Microbiology at the University of Dundee . Later, it was discovered that these fimbriae would re-grow after they had been broken off e.g. by vigorous shaking and that this re-growth was from pre-formed protein sub-units which were stored inside the cells. Fimbriae originate in the cytoplasm of the cell and project through the cell membrane and the cell wall.

| A Controversy |

| A short while after Duguid published his findings an American called Robert Brinton published much the same stuff and called them pili. What followed was a pretty acrimonious exchange of letters in the scientific press about what they should be called.

It was all pretty good fun but to this day our American cousins, and anybody who doesn’t know any better, call them pili whereas all right-thinking, clear-minded and fair microbiologists refer to them as fimbriae. |

So What do Fimbriae Actually do?

Over the years we have learned quite a lot about fimbriae and right from the very early days it was thought that they were involved in helping the bacteria adhere to surfaces. There is now a substantial body of evidence in support of this much of it in relation to pathogenic strains of E coli.

Type I Fimbriae are Pathogenicity Factors

It’s clear these days that Type I fimbriae are involved in bacterial adhesion and the very best example are those carried by pathogenic strains of E.coli. These come in a variety of forms including plain old EnteroPathogenic E.coli (EPEC), EnteroToxigenic E.coli (ETEC), EnteroInvasive E.coli (EIEC) and VeroToxogenic E.coli (VTEC). These E.coli strains use Type I fimbriae to adhere to gut mucosal cells which is the first step in the pathogenic process. Without the fimbriae their capacity to cause disease is greatly diminished or abolished completely.

Type IV fimbriae are particularly interesting. These have also been referred to as “bundle forming pili” because of their ability to aggregate into bundles. These fimbriae are thought to be connected with the ability of EPEC strains to form microcolonies on tissue monolayers and mutants lacking this ability show reduced virulence. Type IV fimbriae have also been shown to be involved in the remarkable phenomenon of bacterial twitching motility which allows bacterial cells to crawl over a surface.

Type VII Fimbriae, Viruses and the Sex Bit

Type VII fimbriae are the conduit for DNA transfer between bacterial mating strains. As it happens they also provide a binding site for certain bacteriophages. The significance of this is a mystery but it does enable Type VII to be seen clearly because when some of the bacteriophage is added to a suspension of cells, the ‘phage coat the Type VII fimbriae. In the electron microscope picture above right you can clearly see little particles stuck on two of the fimbriae which are much longer than the rest because size does matter, at least to E.coli. In a generous attempt to resolve the fimbriae/pili argument it was proposed that Type VII fimbriae were named the “sex pilus”.

|

|

Surfaces of Streptococci

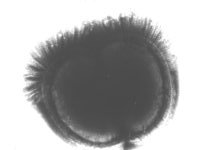

Back in the days before we knew much about fimbriae researchers looking at ultra-thin sections of the serious pathogen Streptococcus pyogenes noticed that the very outside of the cells had a fuzzy appearance. In a fit of imagination it was called “fuzzy coat”. Later, when they learned about shadow-casting whole cells they applied this technique but it did not help to resolve any particular structures like fimbriae.

| S. pyogenes Fuzzy Coat |

|

| Even today we have not resolved any definite structure to the S. pyogenes “fuzzy-coat”. We do know, however, that it consists partly of a substance called “M-protein” which is a major pathogenicity factor of this species. |

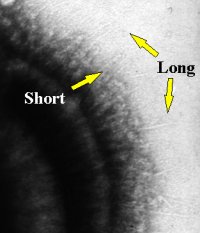

Negative Staining Reveals Surface Fibrils on Some Streptococci

Towards the late 1970s a rather different technique which made use of a special type of stain called a “negative stain” revealed very thin, delicate, hair-like structures on some oral streptococci such as Streptococcus sanguis and Streptococcus salivarius. Take a look at the photograph on the right. This is an electron micrograph of the surface of a Streptococcus salivarius cell and although it may not be terribly clear on this reproduction, the original shots showed two types of these thin hair-like structures, long ones and short ones. This negative-staining technique could not, by the way, reveal anything hair-like on the surface of Streptococcus pyogenes which had the fuzzy coat.

Fibrils are not Fimbriae

More research using lots of different strains of different species of oral streptococci showed these “hairs” came in all sorts of lengths and some cells carried more than one type. They were very thin and flexible. Although some fimbriae on E.coli can be very thin, “flexible” is not a term normally associated with fimbriae. To begin with these hairs were called “fibrils” and there is a fair amount of evidence to suggest they are made of protein and some evidence which suggests that some are even made of glycoprotein although glycoproteins are generally considered pretty rare beasts in bacteria. As far as fibril synthesis goes, we don’t know much. Generally speaking they are difficult to remove, probably because they are so flexible, so it’s not possible to say whether they can re-grow like fimbriae. The analogy was taken a stage further when a role in adhesion was postulated and, in fact, there is fairly good evidence to back this up, at least for the S.salivarius fibrils.

Unfortunately at this point the waters got a bit muddy when some people started referring to the long fibrils as “fimbriae” and the short ones as “fibrils”. Since they are kind of like fimbriae this wasn’t so surprising but what was surprising was that they were never referred to as pili!

| Streptococcal Fibrils |

|

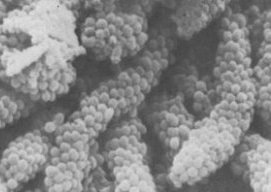

| Some Oral Streptococci Have Tufts of Fibrils |

|

| Some strains of oral streptococci were found to carry tufts of fibrils and looked rather like punk-rockers with Mohican hairstyles. Later these were grouped together into a new species and given the rather elegant name Streptococcus cristae. |

Fibril Tufts and Co-aggregation

There is evidence that these may also be involved in adhesion, this time to rod-shaped bacteria to make the structures commonly found in mature dental plaque called “corn-cob-configuration”. When bacteria of the same species stick to each other it’s known as “aggregation”. In this case the bacteria are from different species and it’s known as “CO-aggregation”.

| “Corn Cobs” in Dental Plaque |

|

And finally

You may have guessed by now that I’m a bit skeptical about using the term “fimbriae” to describe the surface structures of these oral streptococci. I prefer to describe them all as fibrils but I’ll probably end up in the minority. Sooner or later this is all going to be resolved but for the time being it’s probably best to keep the term “fimbriae” reserved for those brittle hair-like, proteinaceous surface projections of Gram-negative rods like Escherichia and Salmonella and call everything else “fibrils”.

Just remember pili are fimbriae and fibrils are different and you won’t go far wrong.

|

|

||||||||||||||||

http://www.ncl.ac.uk/dental/oralbiol/oralenv/tutorials/fimbriae.htm