| Potato Osmosis |

Introduction:

A shipwrecked sailor is stranded on a small desert island with no fresh water to drink. She knows she could last without food for up to a month, but if she didn’t have water to drink she would be dead within a week. Hoping to postpone the inevitable, her thirst drove her to drink the salty seawater. She was dead in two days. Why do you think drinking seawater killed the sailor faster than not drinking any water at all? Today we explore the cause of the sailor’s death. We’ll prepare solutions of salt water to represent the sea, and we’ll cut up slices of potato to represent the sailor. Potatoes are made of cells, as is the sailor!

Objective:

The concentration of solute in a solution will affect the movement of water across potato cell membranes.

Materials:

potato, corer, 3 plastic cups, marker, salt, sugar, distilled water, paper, pencil, electronic balance, clock with second hand or timer, metric ruler, small ziplock plastic bag, foil or plastic wrap

Procedure:

Day 1

- Use a knife to square off the ends of your potato. Your potato’s cells will act like the sailor’s cells.

- Stand your potato on end & use your cork borers to bore 3 vertical holes.

- Remove the potato cylinders from the cork borer & measure their length in centimeters.

- Cut the 3 potato cylinders to the same length (about 4 -5 centimeters long).

- Record the length & turgidity of the potato cylinders in your data table (day 1).

- Place the 3 potato cylinders in a small ziplock bag to prevent them from dehydrating before they’re used.

- Take 3 plastic cups and label them with the solution that will be placed in each one — sugar, salt, distilled water.

- Prepare a saturated solution of salt by mixing as much salt as you can with water.

- Repeat this step by making a saturated sugar solution.

- Now fill each cup 2/3’s full of the correct solution —- sugar water, salt water, or distilled water.

- Mass each of the potato cylinders & record this mass in grams on your data table.

- Place one of your potato cylinders into each cup and cover the top of the cup with foil or plastic.

- Leave the potato cylinders in the solution for 24 hours.

Day 2

- Carefully remove the potato cylinder from the distilled water solution & pat it dry on a paper towel.

- Measure the length of the potato cylinder & record this length & the appearance of the cylinder on your data table. (day 2)

- Measure & record the mass of this cylinder.

- Repeat steps 13-15 for the potato cylinders in the salt solution & the sugar solution.

- Clean up your equipment & area and return materials to their proper place.

Data:

| Results of Osmosis in Potato Cells | |||||||||

| Solution | Initial length cm (day1) |

Final length cm (day2) |

Change in length cm |

Initial Mass g (day1) |

Final Mass g (day2) |

Change in mass g |

Initial Turgidity (flaccid or crisp) |

Final Turgidity (flaccid or crisp) |

Tonicity of Solution (iso-, hypo-, or hpertonic) |

| Distilled water | |||||||||

| Salt Solution | |||||||||

| Sugar Solution | |||||||||

Results & Conclusions:

1. Did any of the potato cylinders change in their turgidity (flexibility), and if so, which ones changed?

2. Explain why the flexibility of the potato slices changed.

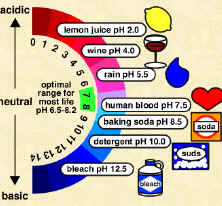

3. Define isotonic, hypotonic, & hypertonic solutions.

4. If potato slices changed in length or turgidity, what process was responsible for this?

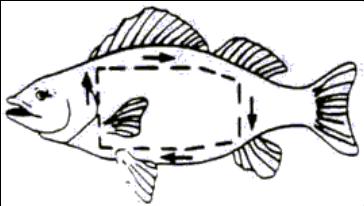

5. Make a sketch of your potato cylinder in the distilled water and use arrows to show the direction of water movement across the potato cell membranes.

6. What type of solutions were the salt & sugar solutions. Explain how you know this.

7. Which solution served as the control for this experiment & why?

8. In which solutions was their a greater solute concentration outside of the cells?

9. In which direction did water move through these cell membranes?

10. In what type of solution do plant cells do best & why?

11. Using the information you’ve discovered from this experiment, explain why the sailor died that drank saltwater.